Hush-a-bye, my baby, slumber time is coming soon

Rest your head upon my breast while mama hums a tune

The sandman is calling when shadows are falling

While the soft breezes sigh as in days long gone by

Way down in Missouri where I heard this melody

When I was just a little baby on my mama's knee

The old folks were humming, the banjos were strumming

So sweet and low

In loving memory of my mother,

and to my father

PROLOGUE

There’s something about it I can’t shake.

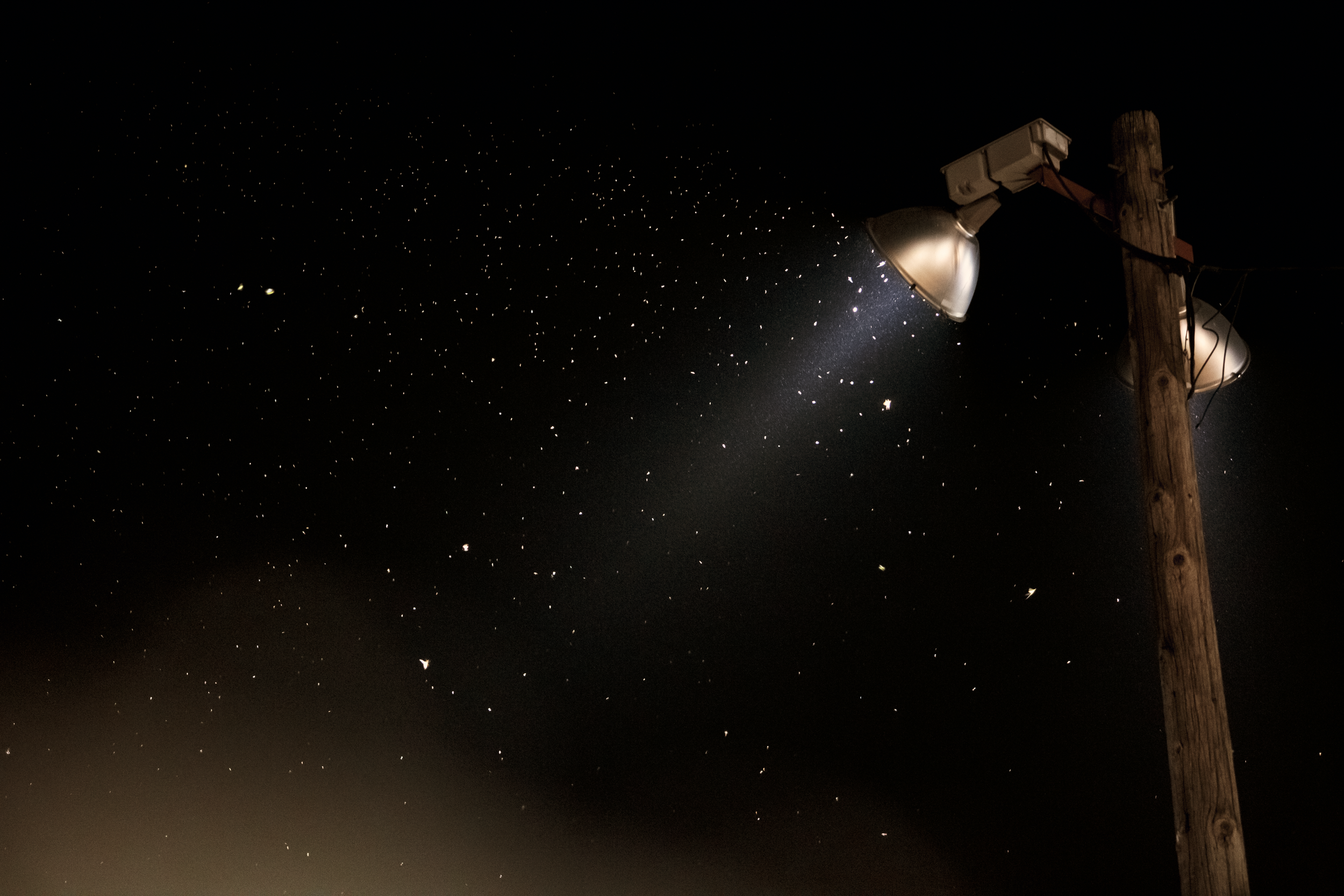

My childhood home in Missouri sat a mile from the storied Saint Charles Speedway dirt track. On Sunday nights, engines bellowed from the horizon through my bedroom window.

I couldn’t see the track, but I felt it, stirring in my chest and throat like thunder buried in the earth.

Up close, the derby was spectacle—fun, cheap thrills for the family. But from a distance, even as a child, I sensed something more. Something beautiful in quiet desperation. A longing in the wail of machines and men.

Thirty-some years later, I still chase the sound. That feeling. I don’t know exactly what compels me. It feels older than nostalgia, familial maybe. It’s like a memory without language. Blood remembering where it came from.

So I stand in the belly of it, trying to remember.

TO THE BONE

Demolition derby is ritual. Destruction as an act of defiance.

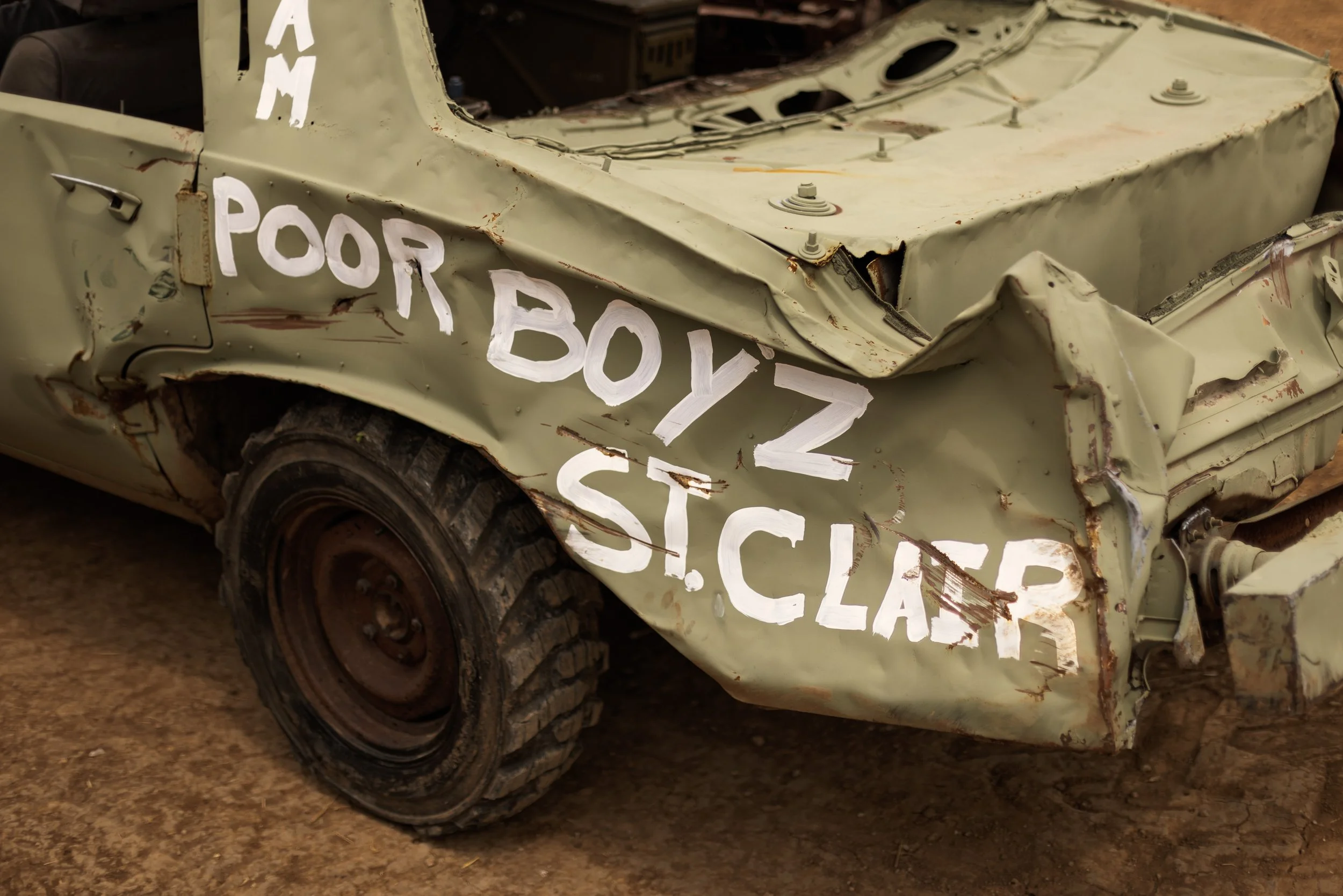

Highway ghosts resurrected, stripped to the bone, armored for war.

Bearing the family name and colors, they enter the arena before their community, beside neighboring legacies, colliding in a tempest of emotional fire until nothing remains but a man’s will. It is a exhibition of resilience against chaos. A purge of something long held in the heart of America.

Artistry hides in craftsmanship. Welds like sutures, engines tuned like hearts, traditions held fast by bolt and steel wire.

A car marked by a stick on the A-pillar is live—poised for engagement. To break it off is to surrender.

Flags rise like law, and fall like commandments. Victory goes to the last man or woman standing, with a nod to their final foe. And to the wildest combatant—perhaps the highest honor: the mad dog award, often decided by roar of the crowd.

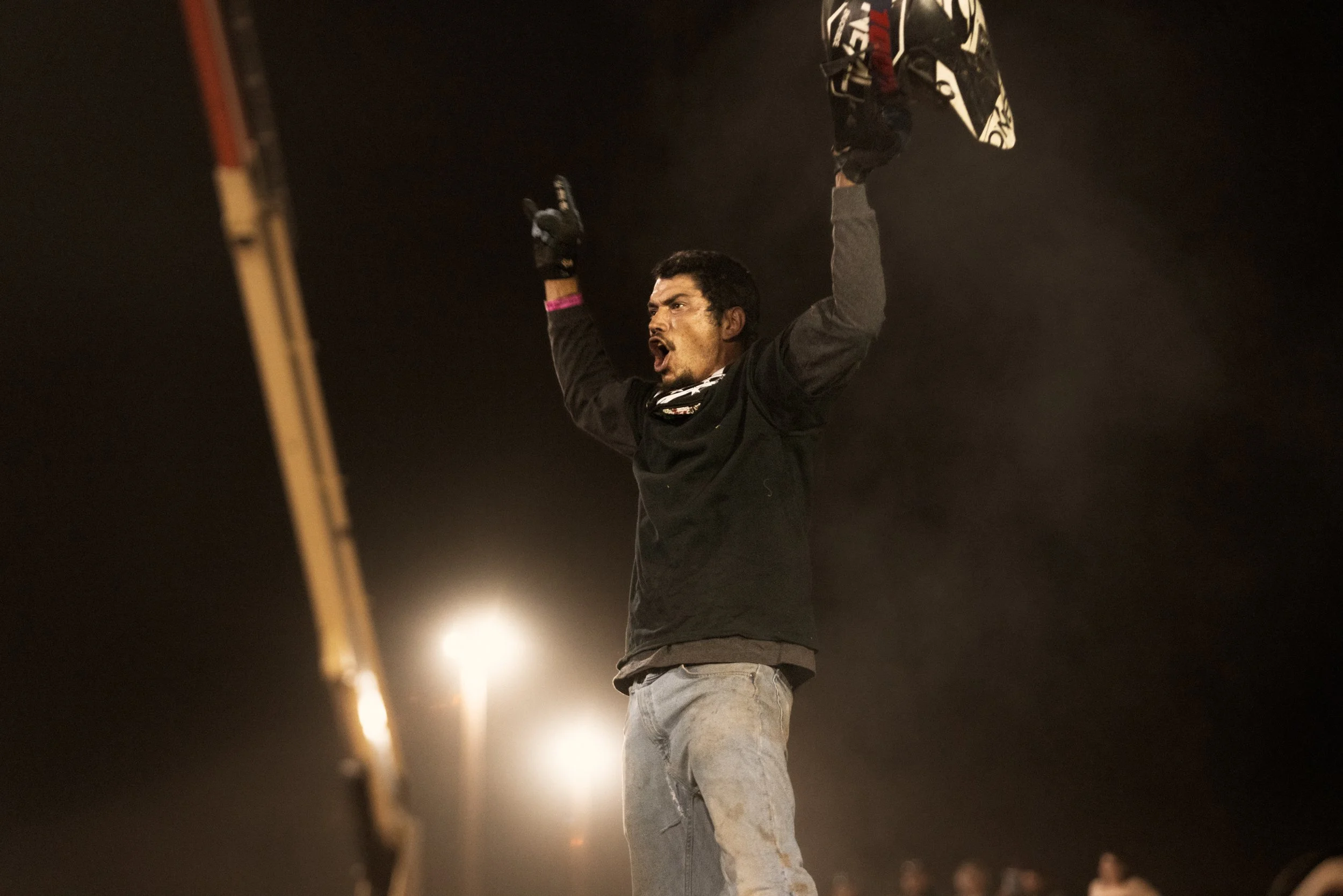

When the dust settles and quiet regains its breath, drivers reemerge from their war machines—blood-hot, white-eyed, soaked to the bone. They shout. They embrace. Bound by a respect only known to those willing to enter the arena, to wager themselves against the palpable threat of violent reality. Alliances are forged. Rivalries sharpened. Tempers spent and set aflame again for another year.

Sacrifice is this communion.

BAX

I met Greg Bax in the shade of two pickup trucks in Warren County, Missouri, 2024. Carpenter shorts, work boots, a ragged tee shirt with his name airbrushed across it. The type of relic that would fetch hundreds at some vintage popup in Los Angeles.

He smoked slow, pulling cigarettes from his chest pocket. Built custom homes, he said. “Only jobs 800 and above.”

When I mentioned St. Charles Speedway, he looked at me sideways, like I’d named a ghost. A grin spread across his face. “I used to make a lot of money out there.” I felt less the nuisance of a mosquito at his head now; more the presence of an equal.

We talked a while. I made pictures.

He poured a can of beer into a steel coffee thermos. “They don’t want you to,” he said. “But a couple beers gets you tuned up. Loose. You put on a better show.” He ditched the empty can into the truck bed. “And if we’re not here to put on a show, what are we doing here?”

I didn’t know what to say to that. I had absolutely nothing to say to that.

We stood quiet. Bax blew smoke into the air. For the first time in years I stopped worrying about making pictures. Somehow I knew I was doing exactly what I needed to be.

A boy ran up asking for his autograph.

“I’ll see you out there,” I said. “Give ’em hell, Greg Bax.”

He winked.

GEORGE

If spectacle is the high watermark of a derby driver, George is the best I’ve seen.

Troy, Missouri. Summer 2024.

I had just gotten to the Lincoln County Fair derby pits when a wiry, shirtless man I didn’t recognize brushed past. Eyes fixed, shoulders hunched in an urgent stride. He had a familiar frequency to him. The tune of a man keeping ahead of his own nerves, running on more voltage than sleep could ever offer. As a photographer, you develop an instinct for such a character.

A minute later, I’m saying hey to some friends when I noticed the speed-walker doubling back on his beeline. “Hey, George!” one of the guys in my group hollered.

He spooked, breaking stride and snapping his gaze toward us like he’d just been found out. He scanned for a familiar face, focused his eyes, then tossed his head back with a sly chuckle of relief. Then he noticed me, ditched the smile, and nervously jammed the glass pipe in his hand into a pocket. That’s when I noticed the ankle monitor. He snapped back and darted off like a caffeinated ghost.

“That’s George?”

“That’s George.”

Later that night, a black Honda with ELIMINATOR spray painted down its side tore through the compact class as if lifting off the gas was never an option. For ten straight minutes the car redlined, buzzing like a million amphetamined hornets propelling an empty Monster Energy can around the track, smashing into anything it had an angle on, friend or foe. I got the impression the ELIMINATOR would crash into itself if it could.

The track announcer, Lincoln County, and I all wondered: Who the hell is that guy?

With two cars left, the ELIMINATOR’s engine finally blew. The crowd deflated, having been on the edge of their seats not for the contest itself, but captivated by just how much one car could take. Out of the smoke plume jumps George, now buzzing with an extra surge of adrenaline. The track announcer gave the winner his moment, but none of us heard a word he said. Lincoln County wanted to hear from the ELIMINATOR.

George is from Terre Haute, Indiana. An out-of-town friend brought in like a secret weapon by a local team called the Honda Mafia. After his speech I jumped the barrier and introduced myself. The following week I caught up with him at another derby.

George doesn’t have a phone. No social media. Hell, George doesn’t have a driver’s license. You don’t get a hold of George. George gets a hold of you, and you thank the derby gods for steering him into your lane.

Hang around derbies long enough and you start to understand what motivates a driver. To some, it’s sport. A craft to be refined and mastered in the spirit of competition. For others, it is spectacle. A good time. A night of fun for the county fair grandstands.

Then there’s a third kind. A rare breed. The men who don’t drive for sport or fun, but out of necessity. Because they have to. Because head-on collisions at thirty-five miles an hour are a type of bottled chaos they can keep a lid on. Disorder they can orchestrate. One that keeps life burning fast at a high octane without taking them under.

George drives like he lives life: fast and unflinching. Keeping on the move, because whatever danger may lie ahead pales in comparison to what might catch up if he slowed down.

One look into his pale blue eyes and you can feel the tempest stirring.

THE NICKLES FAMILY

No account of my derby experience would be complete without mention of the Nickles family.

PLACEHOLDER TEXT

PLACEHOLDER TEXT

PLACEHOLDER TEXT

PLACEHOLDER TEXT

PLACEHOLDER TEXT

PLACEHOLDER TEXT

PLACEHOLDER TEXT

PLACEHOLDER TEXT

PLACEHOLDER TEXT

PLACEHOLDER TEXT

“I’m just an old country boy.”

- Jerry Nickles

FAMILY

The demolition derby tells many stories. But the one that struck me most is the story of family.

Fathers, sons, and grandfathers work and drive together, passing down traditions, donning the family name, number, and paint colors of generations past. Wives, daughters, and children are always present—sometimes riding shotgun, sometimes taking the wheel themselves. Pride, skill, and memory travel through the family bloodline, each hit and turn a lesson in loyalty and courage.

There is real legacy on the line. One bad hit to a father’s driver-side door can echo for a decade, carried on by sons and daughters who never forget. Rivalries are inherited as naturally as the numbers on a car, but so is respect. Old grudges may flare, but shared danger often reveals kinship stronger than any outsider could hope to forge.

With three cars left, families may fight side by side, defending one another, their county, their name. Bonds forged in the mud and chaos endure beyond the scoreboard, carried forward into the next generation, waiting for another derby, another year.

Respect is earned, and respect endures. The derby always ends with a handshake, a smile, and a promise: the story continues, in blood, in steel, in family.

HIGH FIRE

If pain is the touchstone of spiritual growth, the demolition derby driver is a penitent. Not to silence, but to chaos he swears himself. Each night a ritual. Each hit a penance.

Behind the wheel he meets himself. Unearthed. Stripped of illusion. The soil is his altar. The grandstands, his cathedral. Tradition, his scripture. High fire blooms from molten exhaust pipes as he shouts his sermon.

By the body of man and machine—blood spent, battered, unyielding—he makes his sacrifice.

TEMPEST

noun

A violent storm

That’s how I see it: a storm—of debris, chaos, emotion. Colliding, whipping, cracking like lightning with thunder on its back, furious and beautiful.

It begins coiled beneath the earth, humming in anticipation. A calm heartbeat before a storm you paid to witness but could never expect. Summoned, exhumed, the winds form a vortex—serpentine, contracting, expanding, consuming every sympathetic pulse.

This motion is ancient: the ghost dance, the Sufi whirling, African trance, capoeira roda, the mosh pit, the ant death spiral. The instinctive rhythm of life, death, rebirth—the Ouroboros, the universe in motion.

Now in full swing, she becomes sentient—Mother Catharsis. Each of us releases something sacred, feeding the storm. The tempests within and around us merge—communal, collective, alive.

Witnessing her, we are transmuted. For a moment, we ascend.

“Tempest, Tempest…” some said. “I picture a woman, a seductress. A temptress!”

That’s it. Tempest, temptress, empress—it’s all the same thing.

Or maybe it’s just a bunch of fucking hillbillies crashing cars. Don’t do acid at the derby.

QUIET

July 28, 2025. St. Charles County Fair, Missouri. My hometown.

That night it ended. I rode shotgun in the minivan class to open the show. My dad and fiancée in the grandstands. In my pocket, my mother’s photograph.

It was near midnight by the final event. Bone-deep exhaustion weighed on me, my body spent from a month on the road. Every camera and lens I owned, caked with mud, the dust and grime of countless tracks in my eyes, hair, and teeth.

Thunderstorms rolled in. Lightning clawed the sky, burning in a purple glow, black trees silhouetted on the horizon. I was trackside, chest to the ground, the land I came from—making my final photographs. There was a finality to it—not that I was finished, but that something was finished with me. The tempest had loosened her grip.

I felt myself molting, crawling out of this skin. This world fracturing and fragmenting, crumbling away like a dream. I set the camera down, laid my head on my hands, and closed my eyes. The sky broke open. Raindrops on my neck. Two cars left, heaving their final blows, stirring the ground, summoning that familiar song. My heartbeat pressed against it.

And for the first time in nearly a decade, it was quiet.

Hush-a-bye, my baby, go to sleep on mama's knee

Journey back to these old hills in dreams again with me

It seems like your mama was there once again

And the old folks were strumming that same old refrain

Way down in Missouri where I heard this lullaby

When the stars were blinking and the moon was shining high

And I hear mama calling as in days long ago

Singing hush-a-bye